When one executive Localization stakeholder pushes to replace the TMS with LLMs ...

The best thing about Christmas is family.

The worst thing about Christmas is… family 🙂

And this paradox explains quite well how I feel about the dinner on December 31st. That night we all get together at my sister’s place to say goodbye to the year. There are people I see all the time: my sister, my nieces. And then there are cousins, brothers-in-law, sisters-in-law that I basically see once a year. Sometimes we also meet at a birthday, but overall, no more than a couple of times per year. Christmas dinners usually have a bit of controversy. We rarely escape that.

Let’s be clear: it’s not a war like episode 6 of The Bear (have you seen the series? I love it, and that Christmas dinner episode is brutal 🙂). No, we don’t reach that level. But there are always comments that catch my attention.

This year, I keep three “controversies” from that dinner:

The first one was electric cars.

The second one was Pedroche’s dress (if you don’t know what this is about, let it be. You don’t need to know, and I envy you for not having to debate Pedroche’s dress at the last dinner of the year).

The third one, and this one hits closer to home, was AI …and translation.

At some point during dinner, my brother-in-law told me something that was clearly directed at me. He said he had read that real-time translation in the new iOS, with the new AirPods, works really well. He also told me that he uses ChatGPT to translate texts, and that it does a great job.

Let’s pause here for a moment.

Not to discuss whether AirPods have broken the language barrier forever or LLMs, but to talk about something else: brothers-in-law giving opinions about everything.

In Spanish, this is actually a thing. We even have expressions like “no me seas cuñado” or “conversaciones de cuñado”. I don’t know if this exists in other cultures or even if it has an equivalent, but in Spain, when someone gives strong opinions about a topic they don’t really know much about, we call it el efecto cuñado.

What I didn’t know is that this is actually a cognitive bias.

Reading an article titled:

I discovered that this popular saying is actually a well-known bias: the Dunning–Kruger effect.

This phenomenon was identified by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999. Their studies showed that less competent individuals not only make more mistakes, but also fail to recognize their own lack of skill. This suggests that individuals with less knowledge are often the most confident, while those with more knowledge tend to be more humble about their abilities.

So there I was. On one side, enjoying a nice glass of wine and some very good Iberian ham, and on the other, trying to explain why AI has not solved (at least not yet, in my view) the “translation” problem.

With this post, I want to explore two things.

On one hand, to reflect on this efecto cuñado.

On the other, how we can push back in situations like this thinking if we get this “efecto cuñado” not from our brother in law but from our stakeholders, mainly from the C-suite

Because let’s not forget something: when a stakeholder approaches a Localization Manager and says,

“I’ve heard that with ChatGPT we can do automatic translations, so we should use LLMs to translate our app/software / website…”

What we are seeing in action is exactly that: an efecto cuñado. Or, if we want to sound more professional, the Dunning–Kruger effect. Someone stating something with a lot of confidence, even if their knowledge is not very deep.

When confidence comes before knowledge

The key idea in this paradox is that confidence does not always equate to competence.

One of the most important findings of Dunning and Kruger was not only that less competent people overestimate themselves, but also why they do it. They lack the skills needed to detect their own mistakes. In other words: if you don’t know, you also don’t know that you don’t know.

This explains why someone can talk with total confidence about a complex topic after watching a three-minute video, reading a headline, or listening to someone “who knows a lot”. There is no bad intention here. In fact, many psychologists say that the efecto cuñado works like a defense mechanism.

Believing we understand the world is comforting. Doubt is uncomfortable. Ambiguity is exhausting. Admitting that a topic is beyond us makes us feel vulnerable. So, often without realizing it, we prefer a simple and clear explanation… even if it’s wrong.

Seen this way, the efecto cuñado is not just a cognitive bias. It’s also a kind of defense mechanism that reduces anxiety, increases the feeling of control, and reinforces personal identity. The problem arises when this false confidence gives rise to resistance to learning, listening, or revisiting one’s beliefs.

So the question adapted to our Localization industry becomes: how do we deal with this when a stakeholder tells us,

“Let’s use LLMs to localize everything. They are clearly better than translation memories and all that.”

This often shows very high confidence with a limited understanding of how localization really works.

The reason this fits the Dunning–Kruger effect is that they perceive the output quality of LLMs as the primary issue. However, everything that happens behind the scenes is what makes localization more complex than simply plugging in the latest LLM.

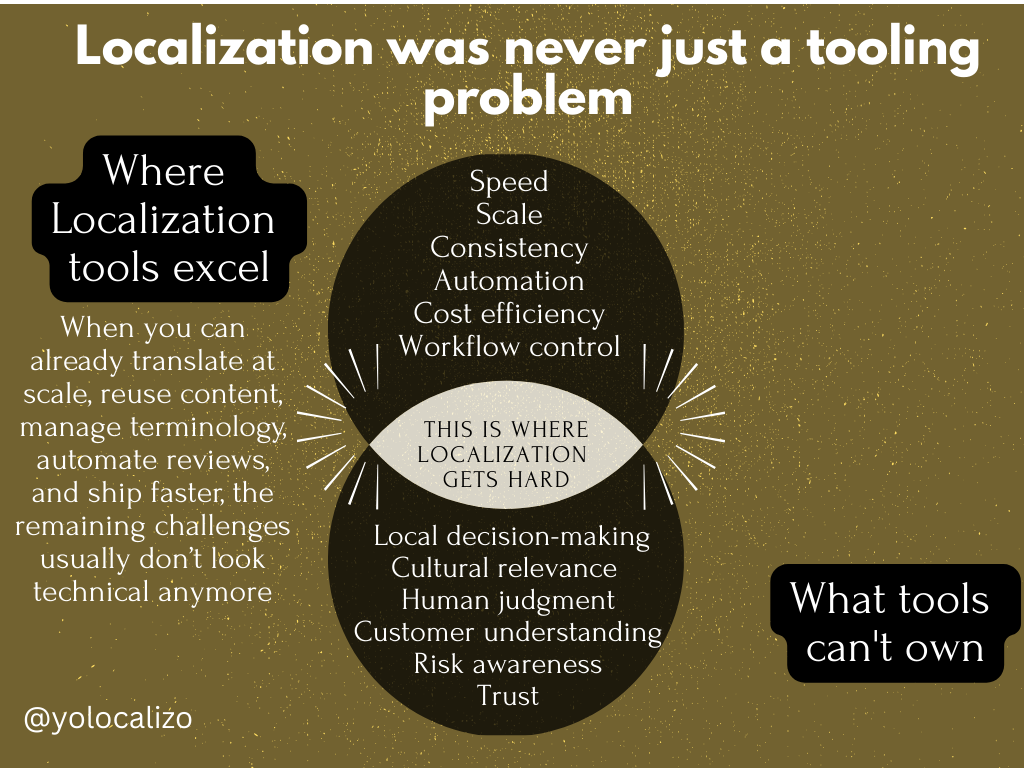

What they usually don’t see (and we do) is that you need to deal with:

Terminology control, consistency over time, legal and brand risk, source changes and versioning, cost at scale, glossary maintenance, LQA…

So, what happens when someone wants to discard our TMs, overlook how we’ve been doing localization, and transition everything to LLMs because it’s cheaper and of better quality?

Keep reading. Below are a couple of ideas that can help in New Year’s Eve dinner conversations… or in meetings with the C-suite, where aligning expectations early can set the tone for what comes next.

Click HERE to downlaod the infographic

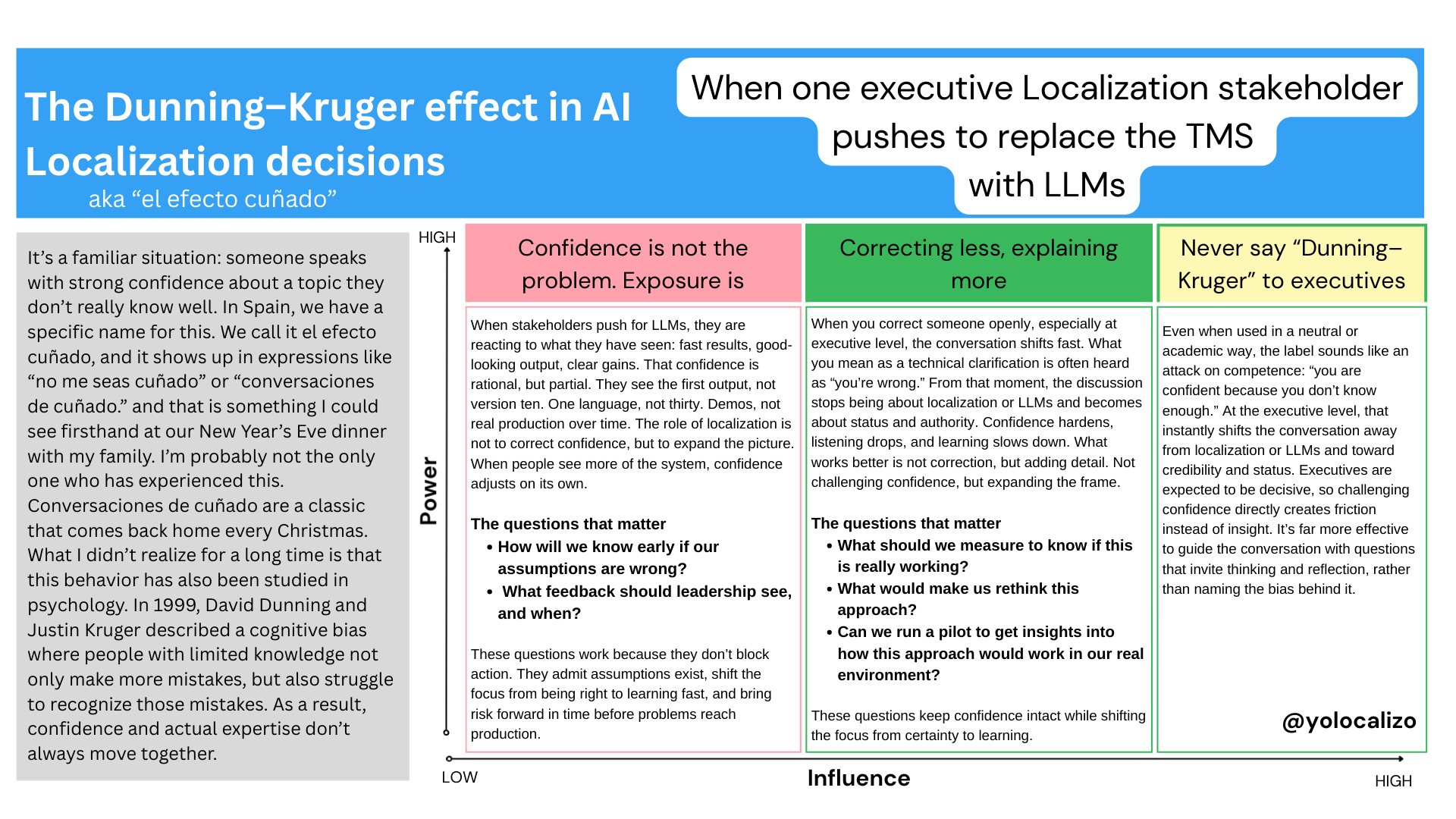

1. Confidence is not bad. Lack of exposure is.

Confidence itself is not the problem. Most stakeholders pushing strongly for LLMs are not reckless or naive. They are reacting to what they have actually seen: fast results, good-looking output, clear productivity gains. From that perspective, their confidence is rational.

The problem is that their view is partial.

What usually gets attention is the visible part: the first output, the demo, the quick win. What stays out of sight is everything that comes after, how translations age over time. What happens when the source changes for the tenth time. How things behave when you move from one language to many, or when the system has to live inside real production workflows. That’s where most localization problems actually show up, and that’s the part people rarely experience firsthand. For that reason, our role is not to tell them they are overconfident. Our role is to add what is missing from the picture. Show how the system behaves over time. Bring in edge cases. Surface downstream effects like legal, brand, or operational impact.

When people see more of the system, their confidence adjusts on its own. No confrontation needed.

Questions that help in these situations are things like:

“How will we know early if our assumptions that LLMs are better than our current Localization approach are wrong?”

“What feedback should leadership see, and when?”

These are strong leadership questions because they accept uncertainty without slowing action. More importantly, they don’t position us against AI LLM implementation because they do three important things:

They admit that assumptions exist (which is always true)

They shift the goal from being right to learning fast

They bring risk forward in time, when it’s still cheap to fix

With LLM decisions, early success can hide problems. These questions force teams to define signals, not just outcomes. Instead of waiting for failure in localized, we agree upfront on what “something is off” looks like.

Dunning–Kruger is not fixed by lowering confidence. It is fixed by increasing visibility.

2. Direct correction creates resistance

Direct correction almost always creates resistance. The moment you correct someone openly, they feel challenged, they start defending their position, and they stop listening. This is even stronger at executive level, where confidence is part of the job.

When you say “that won’t work” or “it’s more complex than that,” what the other person hears is: “you’re wrong.”

At that point, the discussion is no longer about localization or LLMs. It becomes about status and authority. And this is exactly where the Dunning–Kruger effect gets worse.

What works better is not correction, but explanation of the details.

Not “you’re missing the risks,” but “there’s one more layer we should factor in.”

Not “LLMs can’t replace TMs,” but “LLMs solve a different part of the problem.”

This keeps confidence intact while expanding understanding.

Some questions that help here:

“What should we measure to know if this is really working?”

“What would make us rethink this approach?”

Can we run a pilot to get insights into how this approach would work in our real environment?

They focus the conversation on learning, rather than certainty.

One last suggestion

Never say “Dunning–Kruger” to executives.

Even if you mean it in a neutral, academic way, the label carries an implicit message:

“You are confident because you don’t know enough.”

At executive level, that lands as an attack on competence, not as a useful insight. Once that happens, the conversation stops being about LLMs or localization. It becomes about credibility and status.

Executives are trained to be decisive. Questioning that directly creates friction.

It’s far better to use questions to spark thinking, debate, and reflection than to attack knowledge or confidence.

Final thoughts

Ultimately, the Dunning–Kruger effect is not a personality issue. It’s a visibility problem. People decide based on what they see. It’s about how people form opinions when they only see part of the picture. At the dinner table, that’s mostly harmless. In localization, it has real consequences. Our job is not to win arguments or prove anyone wrong. It’s to help others see more of the system, more of the trade-offs, and more of what happens over time. If we do that well, confidence usually recalibrates on its own. And then we can all go back to enjoying the wine, the ham… and maybe even the conversation.

@yolocalizo

The world of localization is full of small, hidden details.

Some things are deeper than they seem, and I often see between in-context review and LQA in the world of Localization. They might seem the same, but if we scratch beneath the surface, we'll see they're not what they seem.

In this post, I want to focus on explaining the differences between in-context review and LQA, which is something I see being confused quite frequently, and although the tasks are similar ... they are not the same.