Why customer insights in English are not enough for global products

My September ritual

Every early September, I look forward to Apple’s presentation of new products. I’ve always been a fan of Apple technology, and it has become a small ritual for me: watching or listening live on my iPhone while I go for a walk. This year, I was in Valencia, walking along the beach, a great place to watch without worrying about being hit by a car 😜

It’s something I’ve done for years. I love technology, and I’m always curious to see what Apple brings. Of course, it’s not the same as the old days when Steve Jobs surprised the world with “one last thing.” Now, with all the rumors and leaks, we usually know what’s coming if we follow podcasts or blogs. Still, I enjoy it.

This time, the new iPhone Air caught my attention, a thin, impressive piece of high tech. But just a few days later, I read the news about the controversy in Korea that forced Apple to edit part of its advertising. That made me think about the theme of this week’s post: global insights versus local insights, a variation of the topic of cultural insights, which is a topic close to my heart.

The illusion of listening

Many companies today claim to be “customer-centric.” They run surveys, track NPS scores, hold focus groups, and study customer journeys. Most of these activities happen in English-speaking markets like the US, UK, or Canada.

The problem is that companies then take these insights and apply them everywhere else. The assumption is that if customers like something in the US, customers in Italy, Brazil, or Korea will like it, too.

But culture is not universal. A feature, a message, or even a simple gesture that feels neutral in one country can feel strange ,or even offensive ,in another.

What do we mean by customer insights?

When product teams talk about customer insights, they mean patterns that explain how people use a product, what they like, and where they struggle. These insights often come from surveys and NPS scores, measuring satisfaction or the likelihood of someone recommending the product. They also come from focus groups, where small groups of customers are invited to discuss features, usability, and their first impressions. A third source is product feedback loops, which are structured ways of collecting ongoing input after a launch (for example, through in-app surveys or customer support channels.)

These methods give valuable information. They help companies track whether their product is moving in the right direction, whether customers are engaged, and whether brand loyalty is growing.But they also have blind spots. Focus groups in English tend to reflect cultural habits in those markets,habits that may not translate globally. NPS numbers can look positive in one region while hiding dissatisfaction in others. Feedback loops often collect input from early adopters in English-speaking countries, who do not represent the wider customer base.

The methods themselves are not the problem. The problem is in how narrowly they are applied.

When global means local blind spots

This bias toward English markets creates blind spots that cost companies money, time, and credibility.

A campaign that feels inspiring in English falls flat when adapted to other languages.

A product flow that customers love in North America confuses users in Asia.

A word that builds trust in one market damages credibility in another.

The irony is that companies spend millions listening to customers in English, while ignoring signals from their other ,often faster-growing ,markets.

Case in point: iPhone 17 in Korea

Apple’s launch of the iPhone 17 Air shows why this is a real risk. In most countries, Apple’s ad showed the phone held between two fingers to highlight how thin it is. But in South Korea, this “crab hand” gesture sparked controversy. Locally, it is associated with anti-men groups and carries a mocking meaning.

The backlash was strong enough that Apple quietly edited the Korean ads to remove the gesture.What looked like a simple, elegant visual in the US and Europe carried a cultural weight in Korea that Apple had not anticipated. And it showed the danger of assuming that one market’s feedback can scale to the world.

The untapped source of insights

Localization teams and LSP partners see these issues every day. They are the first to notice when:

Source text is ambiguous and risks confusing customers.

Tone feels off compared to local expectations.

A visual, symbol, or gesture has unintended meaning.

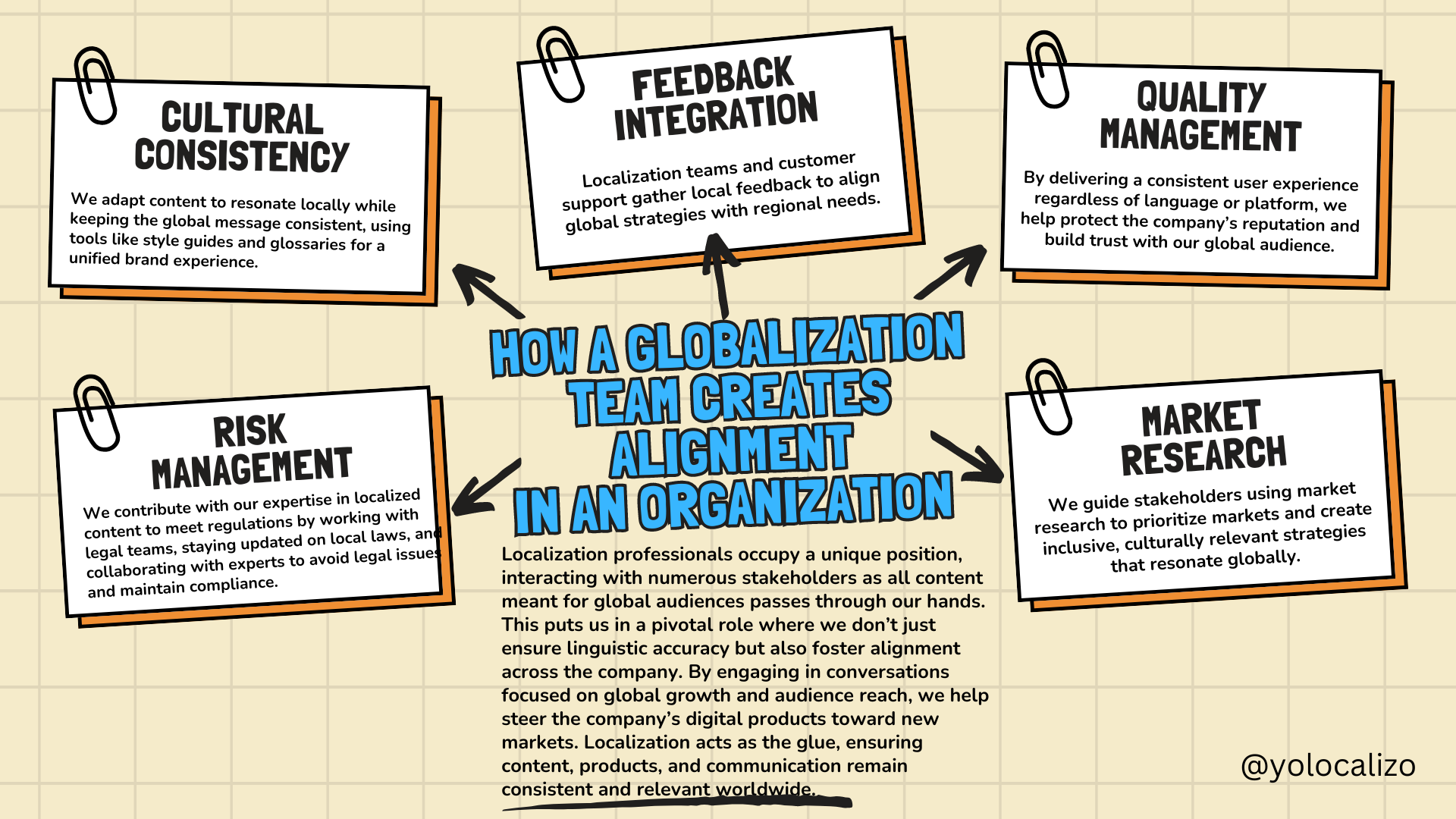

Yet, their feedback often remains invisible. While product teams present dashboards to executives, localization teams are treated as a delivery function, not as a source of intelligence. Why does this happen? Partly, it is organizational: localization usually reports into operations or procurement, not product strategy. Partly it is perception: leaders think of localization as translation, not as a channel of customer truth. And partly it is habit: product teams are trained to listen to metrics, while localization teams deal in context.

The result is a structural blind spot ,one that is predictable, but avoidable.

What real customer-centricity looks like

Click HERE to download the graphic

If companies truly want to be customer-centric, they need to apply the same rigor to international markets that they apply to the US, UK, or Canada. That means:

Building feedback loops per market, not just in English.

Treating localization insights as international customer insights.

Recognizing that local signals are not “exceptions” but essential truths about how people experience products.

This does not mean multiplying research budgets by ten. In fact, one of the common perceptions is that adding more research across markets would be too expensive or too slow. However, the reality is that companies already have listening posts built into their localization workflows. Every time a local team flags confusing copy, highlights a cultural mismatch, or raises a usability concern, they provide customer insight. Ignoring these signals is like ignoring survey data, except it is often cheaper, faster, and closer to the market than running a new focus group.

When localization is part of the process, companies reduce risks and, more importantly, discover new ways to grow.

A game company that listens to localization feedback can adjust difficulty curves for different markets. A fintech company can adapt onboarding to match local expectations of trust. A healthcare company can tailor instructions to cultural norms of clarity and authority.

Being truly customer-centric globally means listening market by market, then bringing those insights together instead of forcing a one-size-fits-all approach.

.A question for leaders

If your company invests millions in hearing the voice of the customer, ask yourself:

Whose voice are we really hearing?

Why do we assume that English-speaking preferences represent the world?

What are we missing by not listening to the local voices already inside our teams?

In conclusion

Customer-centricity that starts and ends in English is not customer-centricity at all. It is a partial view.

The iPhone 17 Korea example is just one reminder that customers do not live in a single cultural frame. True global listening means treating localization insights as market intelligence, not as afterthought.

Until companies embrace this, they will keep hearing their customers ,but only half the story.

@yolocalizo

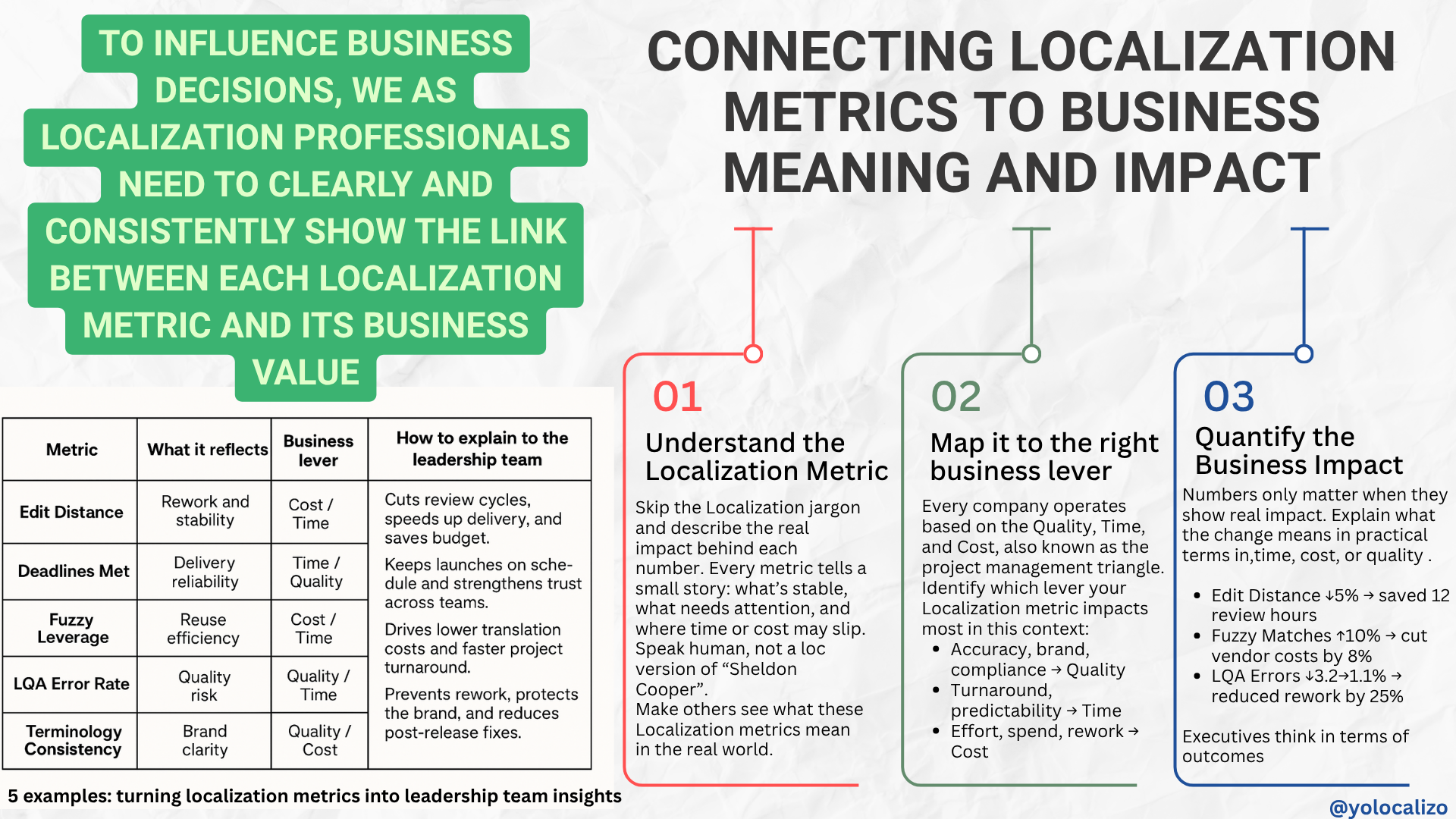

This feels like a pivotal moment. Localization teams are being asked to support more markets, move faster, use AI responsibly, and show impact, not just output. Expectations are higher than ever, but many teams are still trained mainly for execution. We are strong at delivering localization work, yet we often struggle to move from output to outcome and to clearly explain the impact of what we do.